Journal Articles by Eberhard Riedel:

• Psychosocial Complexes: A Human Ecosystems Perspective

By Eberhard Riedel

Abstract: Humanizing the devastating emotional forces released by the worldwide plague of collective violence and trauma demands developing integral awareness. The problems we face cannot be solved at the level of consciousness that created them. I propose a holistic approach that views human communities as complex human ecosystems and individuals as embedded in these environments. To explore the psychosocial properties of human ecosystems I employ a biaxial psychographic map, the Map of the Five Worlds. This map emerged under the press of fieldwork in crisis areas of the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo. The map brings into purview in dynamic mandala format the Familial and Societal Worlds on the horizontal axis, the worlds of Nature and Mind (mind-brain-body system) on the vertical axis, and the Rhizome World at the core. The rhizome world feeds my imagination: It is container and co-created field of humankind’s psychosocial inheritance and codes. We have conscious awareness of only a small fraction of these factors, the rest act autonomically. Community self-states are collective aggregates that involve elements from all five spheres. For my clinical fieldwork I have needed and need ways to understand the dynamic forces of aggregation and evolution that determine a group’s connectivity and tendencies. For example, in community states of collective violence and trauma at extreme levels of severity, the socio-cultural and nature-mind dimensions of the map are “unhinged,” which reflects the fact that in such states nature-nurture and humane-ethical considerations are split off from social behavior and oppressive rhizomic fields dominate the group. Purposeful action intervention seeks to loosen adhesion to the collectivity of suffering, that is, collectivities by which people are connected via emotional resonance with the social emotions of their groups, past and present. Thus the approach raises awareness about the dynamic of cultural seizures as major sources of sociocultural difficulties.

© 2018 Eberhard Riedel. Paper presented at the Joint IAAP-IAJS Conference on Indeterminate States in Frankfurt, Germany, on August 3, 2018. Manuscript submitted for publication in International Journal for Jungian Studies.

• Anima Mundi: The Epidemic of Collective Trauma

By Eberhard Riedel

“Man was not made for himself alone.” ––Plato

Abstract: Epidemic collective violence is perhaps the worst plague facing humankind today. I view states of collective trauma as a contagion because, if left unattended, they dominate people’s thinking and behavior and propagate future cycles of violence. Communities trapped in trauma cycles often are the breeding grounds for severe social problems and chronic violence. Diagnosing collective trauma, as well as research and attempts at finding effective treatments, are in their infancy. Yet we know that the human and societal costs of such trauma are enormous, including that traumatized communities are vulnerable to manipulation and exploitation by leaders with psychopathic tendencies. Radicalization and societal fragmentation have created dangerous situations in many parts of the world, including the United States. Epidemic collective violence is highly contagious; collective splitting generates enormous levels of raw emotional energy and has led, and can lead, to uncontrollable chain reactions.

This article explores the above issues in theory and practice. My case material is based on extensive humanitarian fieldwork in the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo. I offer what I call a non-hierarchical “rhizomic system’s analysis” of community self-states, including states of collective violence and trauma. I find that the complex of collective violence, trauma, and social distress forms a stable self-propagating cyclical pattern. I describe how I evolve a container or temenos for the work, and discuss how I help traumatized communities renew and grow their capacity for curiosity and imagination by setting embodied action into motion. My longer-term goal with this purposeful action approach is to demonstrate that specific purposeful actions can become self-sustaining community-based movements of transformation.

This article is based on a paper presented at the XXth International Congress for Analytical Psychology in Kyoto, Japan, on August 30, 2016.

© Riedel, E. (2017). Psychological Perspectives, 60: 134-155, 2017.

• Time and Again: Transmission of Collective Trauma

By Eberhard Riedel

© Riedel, E. (2015). Video, 2015.

© Eberhard Riedel, "Sexual Violence - Eastern Congo, 2012"

• A Depth-Psychological Approach to Collective Trauma

In Eastern Congo

By Eberhard Riedel

Abstract: Collective trauma is a major public health issue at home and abroad, leaving countless millions dead or physically and emotionally scarred. In this article, by blending Kai Erikson’s sociological perspective with a Jungian-based depth psychological tradition, I develop a multifactorial approach to dealing with complex collective trauma and a paradigm for disrupting the cycles of violence characteristic of collective trauma. In my work in the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) I found that complex collective trauma could not be understood in terms of the symptomatology of the individual trauma survivor. Rather, complex collective trauma spreads epidemically by psychic infection among individuals and communities and across generations. Understanding these complex dynamics requires an approach that is both holistic and specific to the system under consideration.

The dynamic model discussed in this article builds on a paradigm that conceptualizes trauma epidemics in terms of cycles of violence, and intervention in terms of purposeful action that can set into motion cycles of healing. I employ what I call the “purposeful action” paradigm to intervene with a core issue: the propagation of trauma. A pilot study of comprehensive trauma management, the Mobile Clinic Program, has been initiated in three rural areas of South-Kivu Province, DRC, in collaboration with local hospitals and community organizations. The pilot project is designed to test the efficacy of the depth psychological approach to dealing with trauma epidemics. These considerations are broadly relevant to all human rights work and humanitarian aids delivery.

© Riedel, E. (2014). Psychological Perspectives, 57: 249-277, 2014.

© Eberhard Riedel, "Former Child-Soldier - Northern Uganda, 2010"

• My African Journey:

Psychology, Photography, and Social Advocacy

By Eberhard Riedel

Abstract: At home and abroad we face the seemingly intractable problem of fundamentalist ideology, racism and tribal violence tearing apart the human fabric. Here I propose that paying attention to innate psychological processes can make a difference. I work with individuals and communities suffering the post-traumatic consequences of war and violence in crisis areas of eastern Congo, northern Uganda, South Sudan and western Kenya. I have observed that unresolved posttraumatic issues lead to intergenerational transmission of trauma, which, in turn, feeds future cycles of war, violence, and discrimination. In the spirit of prevention, it is essential that the international community prioritize attention to the psychological perspectives involved in human rights issues. Here I develop elements of a holistic systems approach to dealing with large-scale posttraumatic crises afflicting communities and the culture at large. I pay special attention to cultural interfaces and what C.G. Jung called the cultural dimension of the psyche. In fieldwork I blend digital photography and psychotherapeutic approaches to transcend personal and cultural layers of reference and rekindle the struggle of giving birth to one’s future. In a Cameras without Borders workshop a survivor of sexual violence in the eastern Congo said, “The camera is pregnant.” Such metaphors function to shatter limitations of the traumatized mind. Dissociation is the hallmark of psychological trauma as well as the fundamentalist condition. I view developing a capacity for curiosity and mutuality not only as central to the treatment of trauma but also as an antidote to the ills and sclerosis of a fundamentalist mindset, which is the source of much human suffering. Curiosity inspires action and mutuality invites caring about social justice and peace.

Riedel, E. (2013). Psychological Perspectives, 56(1), 5-33, 2013.

• Collective Trauma in Eastern Congo

By Eberhard Riedel

Abstract: The population of eastern Congo suffers from acute post-traumatic illnesses, physical and emotional, in epidemic proportions. Six million people there have been brutally murdered over the past twenty years and no end of the violence is in sight. As a psychoanalyst and photographer I do fieldwork in rural areas of South-Kivu Province, DRC, where I engage in post-trauma debriefing and collaborate with local professionals and volunteers to initiate care for survivors of war and devastating violence. Here I present experiences in four vignettes, each raising troubling questions. The Congolese people cannot discuss their concerns openly for fear of reprisals – such is the climate of collective trauma. In essence I invite the reader to carefully consider their own experiences with the vignettes from a psychological, ethical, social and political perspective. To me ignoring the Congolese situation is to join in collective denial. Modeling principled humane behavior, in private and in public, leads by example and may forge a path to progress in a globally traumatized world.

Copyright © Eberhard Riedel (unpublished manuscript, 2012).

• Fundamentalism and the Quest for the Grail:

The Parzival Myth as a Postmodern Redemption Story

By Eberhard Riedel

Abstract: What is it in the human psyche that lends itself to violent terrorist temptations? My position is that that there is a fundamentalist core in all of us and that liberation is a mutual process. This article presents stories and experiences that shine light on this most critical issue of our time: fundamentalist radicalism and violence. One such story is Wolfram von Eschenbach's Parzival poem that dates back to the era of the medieval Crusades. We will feel the difficulties we face when a deeply entrenched paradigm governing how we relate to ourselves and each other requires change. In the deepest sense this is the task we face with regard to the fundamentalist threat in the world today. Fundamentalist terrorism and warfare represent a total failure of the human spirit. Jung (1934) said, "The only chance for redemption is in consciousness." Beyond this, von Eschenbach (1210) knew that liberation is a mutual process and struggle for humanization. Examples are discussed that show how living with the demand of mutuality can be the basis of a most powerful practice of being and problem solving on both personal and societal levels.

Riedel, E. (2009). Psychological Perspectives 52(4), 456-481, 2009.

• Second Letter from Eastern Congo

© Eberhard Riedel, "Those who are left remember – Eastern Congo, 2011."

In August 2011, writing my first "Letter from Eastern Congo,” I had no idea of the extent to which my fieldwork in South-Kivu Province of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) would change my life. I am not thinking here of the early morning of August 13, 2013, when a gun battle that lasted three hours awakened me to memories of childhood experiences in Germany during World War II. Here, for a brief time, I experienced the chaos that the people of the eastern DRC have been facing, sometimes daily, for the past twenty years.

In my Cameras Without Borders: Photography for Healing and Peace project I engage survivors of trauma in image making both in front and behind the camera (Riedel, 2013, p. 11). The project has evolved and in conflict-ravaged, rural communities of the eastern DRC small groups of local people are increasingly involved in addressing the 'collective trauma' of epidemic violence and genocidal warfare (Riedel, 2014). This work is proceeding in collaboration with professionals and volunteers associated with the Great Lakes Foundation (GLF) for Peace and Justice, Pastor Bwimana Aembe, Director.

Intergenerational transmission of trauma is a serious problem because it fuels ever-more destructive cycles of violence. For example, in a village that had suffered horrible massacres I facilitated a support group for eight former child-soldiers; their average age was 16, but they had spent a total of 43 years in captivity in the bush, on average 5.4 years each. Later I engaged these young men in a psychotherapeutic photography workshop – I describe details of this approach in a journal article on “Psychology, Photography, and Social Advocacy” (Riedel, 2013). One of the young men said to me, “You have given me something more important than money.” As a photographer and psychologist I seek to set into motion processes that help people move beyond being paralyzed by trauma to being able to live with trauma.

Collective trauma dehumanizes individual and community life. In the contested areas of the eastern DRC sexual atrocities and torture are employed as weapons of warfare. In the aftermath, I frequently observe how traumatized communities scapegoat victims resulting in what I call ‘circular oppression.’ My mantra is de-traumatization means humanizing the situation.

© Eberhard Riedel, "After the Attack I & II – Eastern Congo, 2012."

Dehumanization extends to environmental problems. For example, I often observe how traumatized communities lose resilience and connection to indigenous roots and cultural values. Frequently trauma becomes a thinly veiled excuse for exploitation. We are or should be aware of the environmental trauma caused by international mineral exploitation in the eastern DRC. But it is no less disastrous when traumatized communities, for example, turn their old-growth forests into charcoal for sale, destroying the very resources on which their lives depended for centuries. In collectively traumatized communities human and environmental devastation are linked and must be addressed holistically.

The toxic confluence of repercussions of the Rwandan genocide of 1994 and large-scale international mineral exploitation in the eastern DRC have set into motion a human tragedy of unspeakable brutality in which, since 1994, an estimated six million Congolese citizens have died. This is a horror the world widely ignores. Field experiences with my Cameras Without Borders project have convinced me that this overwhelming human suffering is not just a political issue, to be left to military and political solutions, but needs to be approached as a mental and public health problem. I am not the first person warning, “When we imagine that our psychology is separate from politics, we support violent conflict” (Audergon, 2004).

Through my photographic work in the DRC I came to realize that there is no logically foreseeable, linear solution to the complex collective trauma situation there. I began thinking in terms of dynamic patterns…of cycles (Riedel, 2014). For example, healthy situations are characterized by cycles of generativity and collective trauma situations by cycles of violence. Intervention requires interrupting the cycles of violence to help traumatized communities to reconnect with generative energies. It is not about getting it right at first try but about finding a process, which I call purposeful action that sets into motion cycles of healing. To be effective, change in these troubled regions must be homegrown, i.e. emerge from the local environment rather than be imposed from the outside.

When I ventured into South-Kivu Province, DRC, in 2011, over and over in traumatized rural communities I heard women and girls, all survivors of sexual atrocities and torture, ask for “field hospitals” that would tend to their physical and emotional wounds. The plight of child-soldiers, who are also the victims of rampant violence, was not different.

Over the past three years, listening to and working with trauma survivors, doctors at small rural hospitals, and community organizers the idea of a holistic Mobile Clinic Trauma Management project developed. The Pettit Foundation awarded my Cameras Without Borders: Photography for Healing and Peace project at Blue Earth a $50,000 grant. Their generosity is a great example of how partnerships between communities, documentary photographers, and foundations can yield concrete results.

© Eberhard Riedel, "Mobile Clinic I & II – Eastern Congo, 2013/12."

The Mobile Clinic pilot project provides not only medical and psychosocial treatment but also vocational training programs (Riedel, 2014). The project reaches out to rural areas where the Congolese trauma epidemic rages out of control and survivors have no access to medical care and many die. During its first year, the on-the-ground impact of the Mobile Clinic project is helping more than 1,000 survivors of war-related sexual atrocities and torture to access medical and psychosocial treatment. The project also provides seed money to communities for vocational training projects with the dual purpose of social reintegration of trauma victims and economic community development.

The training projects encourage local organizations to develop a sense of independence, decision-making, and acceptance of responsibility for making the Mobile Clinic Program self-sustaining. These expectations are strategically important to empower communities, overcome forces of social fragmentation, and counter the pervasive sense of helplessness and dependency associated with collective trauma: “Detraumatization means humanizing the situation.”

Posted February 28, 2014

Eberhard Riedel, Photographer and Psychoanalyst

"Cameras without Borders: Photography for Healing and Peace" is a Blue-Earth Project.

• First Letter from the Eastern Congo

I recently returned from seven weeks of fieldwork in South-Kivu Province in Eastern Congo, which borders Rwanda, Burundi and Tanzania. Since I started my Cameras without Borders: Photography for Healing and Peace project in Africa I had looked for an opportunity to work in the eastern parts of the Democratic Republic of Congo. This chance presented itself when I met Pastor Aembe, President of the Great Lakes Foundation, who invited me to Eastern Congo to contribute to their group’s peace building efforts. We met in November 2010 while I lectured at Makerere University in Kampala, Uganda, as part of a three-months project in Uganda and Kenya.

Since the beginning of the Rwandan genocide in the early 1990s the neighboring parts of Congo have been in constant turmoil and states of war with terrible consequences for the local population and environment. Travel and photography permits are required, and a continual monitoring of the security situation is necessary while working in rural areas of South-Kivu Province. I was fortunate to have the unwavering assistance of members and associates of the Great Lakes Foundation located in Bukavu, the Provincial Capital of South-Kivu. The Great Lakes Foundation was started by a group of local professionals who have dedicated their lives to peace building efforts in their region.

Though travel in eastern Congo was physically and emotionally difficult, I returned home feeling not only deeply effected by the experiences but also sensed that a page had turned in my professional life – both as a photographer and psychoanalyst. The physical and emotional trauma of the people in the Province is quite overwhelming; the abuses are ongoing and epidemic. As a psychologist I was able to: (i) provide psychological support to some victims of sexual abuse and ex-child soldiers; (ii) work with their families and communities around rejection of sexually traumatized women and issues of reintegration of ex-child soldiers; (iii) refer fifteen of the most seriously injured women to Panzi Gynecological Hospital in Bukavu; and (iv) train local volunteers and professionals.

As a photographer I had two distinct goals: (i) To visually translate emotional experiences into portraiture in order to communicate the multiple psychosocial issues that plague the people of Eastern Congo and neighboring Burundi, Rwanda and Uganda. Out of safety concerns I did most portrait work in private spaces and limited my people-in-environment documentary efforts. (ii) My other goal was to teach photography to individuals who have suffered trauma and are marginalized and to encourage them to tell their stories through images. This process follows an old tradition of building bridges to artistic layers of the psyche to help people rediscover their voice.

Specifically, I conducted Cameras without Borders workshops with three groups of women who had been sexually victimized and three groups of ex-child soldiers. After printing three or four photographs for each participant I typically start the conversation asking, “What are the stories these pictures are telling you?” In the resulting group process most participants spoke quite eloquently from their hearts, which in turn encouraged local professionals to look at group therapy as a healing modality.

Photographic work with victims of war and violence requires reflection on boundary issues - does the work help or exploit the victim? My goal is to help interrupt the cycle of violence. To achieve this I believe we must tend to the physical and emotional wounds of victims of trauma. In Eastern Congo the issue is to help stop a perverse war against the indigenous population and the environment. Collaborating with local people, such as members of the Great Lakes Foundation, who, yearning for peace, engage both in grassroots work and efforts to transform the political and legal culture of the region, provides many opportunities to effect change.

When I meet with people in the villages I frequently ask, “What kind of assistance would be most helpful to you at this time?” Overwhelmingly the first concern is health services. Of the tens of thousands of victims of sexual violence in the rural areas of South-Kivu Province the vast majority go for months or years without access to treatment for their internal injuries and infections, and scores die. The next most frequent assistance requested is help from the international community to remove the quasi-nomadic foreign militia criminals from the bush. The psychosocial consequences of this epidemic are vast: Villagers live under constant threat; women fear returning to their fields where many attacks happen; men feel unable to protect their families, so they feel disempowered and often leave; young rape victims are shunned from marriage; and families lack the funds to send their children to school. The mayor of one village said to me, “Peace starts at the local level with education.” But my observation is that trauma is being transmitted to the next generation and, I fear, this will fuel the next cycle of violence. This is the topic of another Letter from Eastern Congo.

Posted August 4, 2011

Eberhard Riedel, Photographer and Psychoanalyst

"Cameras without Borders: Photography for Healing and Peace" is a Blue-Earth Project.

© Eberhard Riedel, "Up Against a Wall - Northern Uganda, 2011"

Photography Exhibition at the University Friends’ Meeting House

4001 Ninth Avenue NE, Seattle, WA, 98105

Eberhard Riedel

The Photographer as Witness: An Exhibition

© Eberhard Riedel, The Witness, 2012, Kamananga, South Kivu Province, DRC

This exhibition of photographs honors the witnessing other who connects us with our humanity. I invite you to linger over this collection of photographs from a formative period of my fieldwork in crisis areas of the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and northern Uganda. Deeply affected by the human suffering and sensing that “knowing things entails responsibility,” I wondered how I might help dealing with the acute epidemic of collective trauma I was witnessing.

To take you right into the exhibition: The young woman on your right is a former child-soldier, the woman on your left a survivor of genocide, and each of the thirty women, men, and children whose portraits you see here in this Social Hall carry deep emotional and physical wounds of trauma.

Following a call, I have developed a collective trauma management program in the eastern DRC working together with doctors and volunteers at small rural hospitals and grassroots community organizations. I am grateful to these Congolese men and women, including my local coordinator and translator, Lawyer Rod Eciba, for their trust and compassionate work helping their people.

I most gratefully acknowledge generous support from Friends of Cameras Without Borders and the Pettit Foundation, and sponsorship by the Blue Earth Alliance.

Eberhard Riedel

Cameras Without Borders:

Photography for Healing and Peace

October 4, 2015 – December 31, 2015

Social Hall of the University Friends’ Meeting House

4001 Ninth Avenue NE, Seattle, WA, 98105, Tel. 206-547-6449

Hours: Daily except Saturdays, 9 am – 1 pm

Open House and Reception: Saturday, November 21, 2015, 3 – 6 pm

Presentation at Symposium on Transforming Trauma

George Mason University, Founders Hall, Room 111

3351 North Fairfax Drive, Arlington, VA 22201

Eberhard Riedel

The Art of Social Transformation: A Depth Psychology Perspective

This presentation focuses on collective trauma, perhaps the worst plague facing humankind today. In recent years much attention has been given to the study and treatment of traumatized individuals in clinical settings. But here I will address the cyclical relation between psychological trauma, collective violence and serious social problems. With the fragmentation of the core, self-regulating center of traumatized communities the floodgates are open to overwhelming archaic emotions that enter whenever events trigger a collective trauma complex. For example, traumatized communities are vulnerable to psychic infection, and warlords exploit such vulnerabilities to inflame groups against each other. This is just one of many cyclical mechanisms I observed during fieldwork in the eastern DRC that lead to self-propagating patterns of collective and cultural trauma. In a paradigm shift, I concluded that the overwhelming cycles of violence and genocidal warfare I was witnessing are an inherent expression of epidemic collective trauma and need to be addressed as mental and public health problems rather than only as political issues. Working together with doctors and volunteers at small rural hospitals and with grassroots community organizations, I have developed a purposeful action approach to deal holistically with the epidemic of community trauma at three sites in the eastern DRC. The method recognizes the relation between psychological trauma, collective violence and serious social problems. I will demonstrate how purposeful action is energizing these communities to overcome the paralysis of collective trauma and show how it provides a template that offers the potential to effect long-term change across large areas, reaching many people. In short, the goal of this community work is to mitigate cycles of violence by setting into motion cycles of restorative action and healing.

I am grateful for generous support from Friends of Cameras Without Borders and the Pettit Foundation, and sponsorship by the Blue Earth Alliance.

September 26, 2015

George Mason University, Founders Hall, Room 111

3351 North Fairfax Drive, Arlington, VA 22201

Event Information at www.jungiananalysts.org

• Eberhard Riedel Speaking in Santa Fe, NM, Seattle, WA, and Boulder, CO:

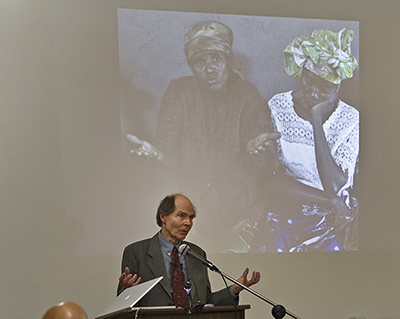

Eberhard Riedel (Photo © Tom Reese)

Eberhard Riedel (Photo © Tom Reese)

Eberhard Riedel is busy traveling, speaking, and presenting workshops about his Cameras without Borders: Photography for Healing and Peace work in Africa. On February 24-25, 2012, Riedel will be speaking at the C.G. Jung Institute of Santa Fe and on March 9-10, 2012, for the C.G. Jung Society of Seattle. You are cordially invited to attend. In Seattle photographers pay discounted membership admission. A third presentation at the I-RSJA Spring Meeting in Boulder, CO, on April 20, 2012, is by invitation only; please contact the speaker for information.

In these presentations Riedel addresses the challenges inherent in empowering and providing psychosocial support to large numbers of individuals and communities that suffer the traumatic consequences of war, violence and marginalization. For the past six years he has worked with such communities in Uganda, Congo, Kenya, and South Sudan in collaboration with African people working to address the psychological sequelae of war and tribal violence. As a psychologist he blends digital photography and old healing methods developing a systems approach to treat psychological trauma. As a photographer he attends to cultural interfaces and strives not only to document and advocate but also to set into motion a process whereby survivors are better able to tend their psychological wounds and communities to interrupt the cycle of violence.

Eberhard Riedel will discuss how his project originated (Santa Fe – Friday Lecture) and how fieldwork in crisis areas in Africa challenges both the photographer and psychologist to find adequate expression and concepts for dealing with the new realities of our time (Santa Fe – Saturday Workshop; Seattle – Friday Lecture & Saturday Workshop). Cameras without Borders is a Blue Earth project.

© Eberhard Riedel, "Survivors - Northern Uganda 2011"

Posted January 30, 2012

Eberhard Riedel, Photographer and Psychoanalyst

"Cameras without Borders: Photography for Healing and Peace" is a Blue-Earth Project.